Modern Politics, Ancient Poison: Labour’s Antisemitism Crisis

- Oliver Lamb

- Jul 29, 2020

- 13 min read

Updated: Dec 22, 2024

In this long-form piece, Oliver Lamb examines the history of antisemitism within the Labour party. Rows were once again ignited after Rebecca Long-Bailey tweeted, what leader Keir Starmer, described as "an antisemitic conspiracy theory". However, the Jewish community's concerns about Labour date back further than this year, and were notably triggered by Corbyn's election in 2015. A small number of those associated with the far-left have been found to circulate antisemitic posts online, and further harmful tropes.

The sacking of Rebecca Long-Bailey on the 25th of June looked, on the surface, like a standard case of misjudgement and consequence.

Long-Bailey was the UK’s shadow education secretary and one of the leading figures in the opposition Labour Party. On the 25th of June, she retweeted an interview with the actress and Labour supporter Maxine Peake, in which Peake claimed that the police tactic of kneeling on a suspect’s neck was taught by the Israeli secret service. Long-Bailey later said that the interview’s “main thrust was anger with the Conservative Government’s handling of the current emergency and a call for Labour Party unity,” and that she did not endorse “all aspects of the article”. By then it was too late. Just hours after the tweet the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, announced that he had asked Long-Bailey to step down.

The move reopened divisions in the party that, in truth, had never really healed.

The seeds of Labour’s antisemitism crisis were sown in September 2015, when Jeremy Corbyn took over as leader. Corbyn had been a Member of Parliament since 1983 but had never held any leadership role in the party; on the contrary, he was considered a fringe figure. A staunch ‘hard leftist’, he voted against the party line 617 times while supporting causes as diverse as nuclear disarmament, trade unionism, anti-apartheid, Palestinian solidarity, Irish republicanism and gay rights.

How did this outsider rise to the top of one of the UK’s two major parties? His opportunity came when, in the wake of Labour’s defeat in the general election of May 2015, leader Ed Miliband resigned and triggered a leadership election. Corbyn entered late and got on the ballot with minutes to spare, but from there his campaign went from strength to strength. Rallies were soon standing-room-only; then he started having to make speeches twice, first to the main audience and then to the crowd who were stuck outside. His secret was fervent opposition to the ruling Conservative Party’s policy of economic austerity that, combined with his anti-establishment image, appealed to thousands of Labour members disillusioned with Corbyn’s centrist and ‘soft left’ rivals.

But that would have counted for nothing if not for a change in the way Labour’s leadership elections are run. Unlike previous contests, anyone could pay £3 to vote in 2015. Almost 200,000 took advantage of the new rules, many of them far to the left of most of the parliamentary party. Their support propelled Corbyn to a comfortable victory.

The influx of leftists continued during his leadership; Labour’s membership soared from 190,000 in May 2015 to 515,000 in July 2016. Many of the new members, however, were strident critics of Israel and its policies towards Palestinians.

Israel as a modern state was founded in 1948 after a decades-long campaign by Zionists – those who support the existence of a Jewish state in Palestine, a small strip of land that, according to Jewish tradition, was promised by God to the Jews. From the 1880s onwards, and especially after the First World War, amid a climate of heightened antisemitism in Europe, hundreds of thousands of Jews emigrated to Palestine. Conflict between Jews and Palestinians escalated until 1947, when the newly-formed United Nations voted to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. Full-scale war followed in 1948. The armistice of 1949 gave Israel a fifth more land than the partition agreement specified; meanwhile Jordan occupied the West Bank, which comprised much of the territory meant to be given to Palestine. 600,000 Arabs fled their homes, many of them ending up indefinitely in UN-run camps.

The Six-Day War of 1967 brought new territory under Israeli occupation – but also more than a million Palestinians. The West Bank and the Golan Heights, along with their people, have been controlled by Israel ever since.

Since 1948, most Western politicians have largely supported Israel while criticising some aspects of its foreign policy. Others, particularly on the left, have been far more critical, even questioning the existence of Israel itself. Many of the state’s defenders maintain that anti-Zionism equals antisemitism. They in turn stand accused of conflating anti-Zionism with antisemitism to stifle legitimate criticism of Israel.

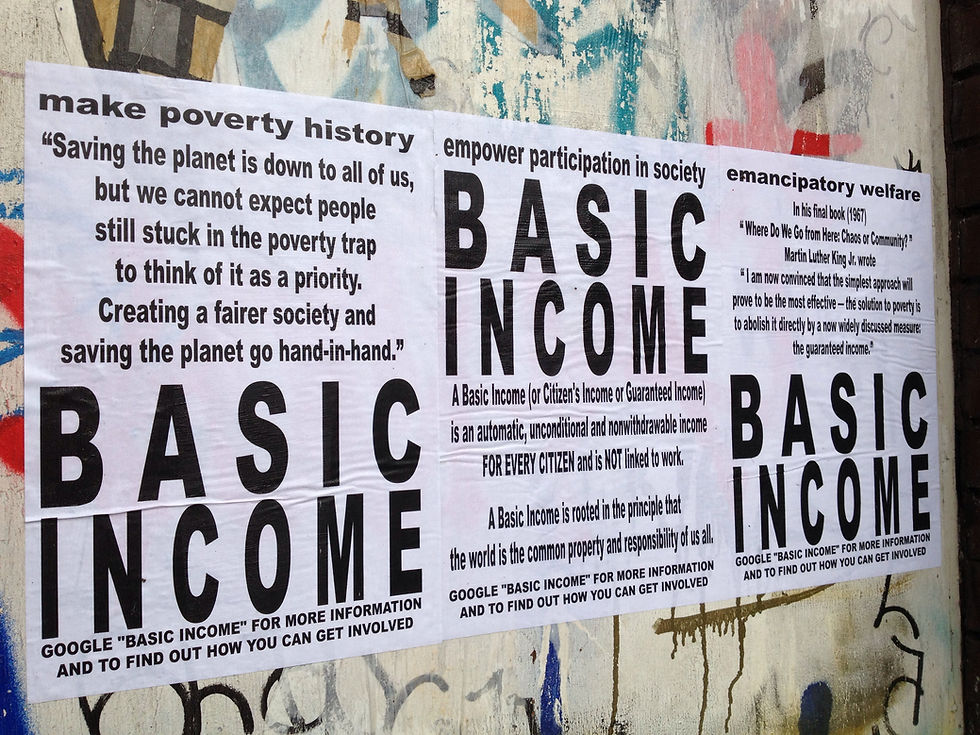

Some of Labour’s new members, however, went beyond legitimate criticism. It was soon pointed out that a small minority of them were using social media to spread antisemitic tropes, stereotypes and conspiracy theories.

During spring of 2016, there were several high-profile controversies. In February, Alex Chalmers resigned from the chair of the Oxford University Labour Club, reporting that some of its members had a “problem with Jews” and expressed support for the Palestinian group Hamas, which is considered a terrorist organisation by Israel, the US, EU, and UK - amongst others. Chalmers dated the rise in antisemitism to Labour’s defeat in the 2015 election.

Another case was that of Vicki Kirby. She had already been suspended in 2014 for a series of tweets in which she declared that Jews “slaughter the oppressed” and have “big noses and support Spurs”. Her appointment to the vice chair of Labour’s Woking branch prompted calls for a second suspension. Corbyn initially refused but relented in March.

In April, the Labour councillor Aysegul Gurbuz was suspended after the discovery of old tweets in which she declared “Adolf Hitler = greatest man in history” and hoped that Iran would use nuclear weapons to “wipe Israel off the map”. However, Gurbuz denied the accusations, and claimed her sister had written the messages.

Things came to a head on 27 April when Naz Shah, a Labour MP, gained notoriety for a series of Facebook posts. In one of them, from 2014, she suggested that Israel be moved to the United States; in a separate post she compared Israel’s policies to those of Hitler. Corbyn was reportedly reluctant to suspend her but was persuaded to do so by the party’s general secretary, Iain McNicol. Shah was reinstated in July.

Among her defenders was the former Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone. Speaking in Shah’s favour on 28 April, he claimed that Hitler had supported Zionism when he came to power in 1933. Livingstone refused to apologise, insisting that his assertion had been historically accurate and that he was not antisemitic. Nevertheless, after a heavy backlash he was suspended. He quit the party in May 2018.

What all these incidents shared was that Corbyn seemingly did nothing unless pressured to. Within months of his assuming the leadership, he had been accused by several figures – including two Labour ex-shadow cabinet ministers, the chairman of the Jewish Labour Movement, a Labour peer and the President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews – of failing to tackle antisemitism. The charge stung because Corbyn himself, as he repeatedly pointed out, had spent much of his life campaigning against racism.

The issue quickly became bound up in Labour’s internal politics. Corbyn argued that the supposed antisemitism crisis was concocted by his centrist and soft left opponents in the party who feared the growing influence of the hard left. His allies labelled it a “witch hunt” intended to undermine him ahead of the local elections in May 2016. Many Labour MPs scorned that suggestion. Michael Dugher, a former shadow cabinet minister, said Corbyn had “prevaricated [over suspending Livingstone] because it was another of their close allies up to their necks in anti-Semitism”. It is important to note that Livingstone supported Corbyn.

In the wake of the Shah and Livingstone controversies, Corbyn asked the barrister Shami Chakrabarti to chair an inquiry into racism within Labour. The report was published in June 2016. It found that the party “is not overrun by anti-Semitism” but that there was an “occasionally toxic atmosphere”, and recommended measures to tackle this. However, in July 2016 Corbyn nominated Chakrabarti for a peerage and in October made her shadow attorney general, leading some Labour MPs and Jewish groups to question the credibility of her report.

The report’s publication was overshadowed by the turmoil now unfolding in Labour. On 23 June 2016, after a bitter referendum campaign, the UK had voted to leave the European Union. Corbyn had supported Remain, but only half-heartedly – he was widely suspected of holding pro-Leave views, yet another issue on which he disagreed with the majority of his party. His lacklustre performance during the campaign triggered a storm of discontent among Labour MPs over the perceived weakness of his leadership. 26-27 June saw twenty shadow cabinet ministers quit and Corbyn had so few supporters that he could not find replacements for them all. On 28 June he was defeated in a motion of no confidence by 172 votes to 40. Nevertheless, he refused to resign.

By July, Corbyn was facing a leadership challenge in the form of Owen Smith. The election was held in September and, thanks again to the one-member-one-vote system, Corbyn swept to a greater victory than he had a year previously, with 61.8% of the vote.

Seven months later he was fighting another election, but, this time, he was vying to lead the country. Prime Minister Theresa May had inherited a Parliamentary majority of just twelve when she took over from David Cameron in July 2016. When she called a snap election in April 2017, the Conservatives held a massive poll lead over Labour and analysts predicted a correspondingly colossal majority. Corbyn, however, proved once again to be a surprisingly effective campaigner, captivating crowds with his anti-austerity message. The contrast with May’s woodenness and apparent coldness was stark. Labour received 40% of the vote (a percentage that had won them a majority of 167 in 2001) and won 262 seats, 30 more than in 2015. The Conservatives won 317 seats, thirteen fewer than in 2015. They were still in power but had lost their majority.

After the better-than-expected election result Corbyn’s leadership was unassailable, but unease over antisemitism did not disappear. In March 2018, the Jewish Leadership Council and the Board of Deputies of British Jews organised a rally outside Parliament demanding action; three Labour MPs were among the speakers. They claimed Corbyn had “sided with anti-Semites rather than Jews”.

In July of that year the UK’s three biggest Jewish newspapers published the same front page, each warning that a Corbyn-led government would pose an “existential threat to Jewish life”.

By this point Corbyn’s personal views on antisemitism were coming under fire. In March 2018 the Labour MP Luciana Berger – a Jew herself – highlighted a Facebook post from 2012 in which Corbyn opposed the removal of a mural that some called antisemitic. The mural, by the street artist Mear One, depicted six men with stereotypically Jewish facial characteristics sitting around a Monopoly board that is resting on the backs of unclothed people. To the left a man holds up a sign reading ‘The new world order is the enemy of humanity.’ Corbyn claimed that he had defended it on the grounds of free speech and had not examined it closely.

In August 2018, he apologised after it came to light that, as a backbench MP in 2010, he had hosted an event in Parliament that likened Israel’s policies to those of Nazi Germany. To add insult to injury, the event took place on Holocaust Memorial Day. He conceded that he had shared “platforms with people whose views I completely reject”.

Two weeks later, pictures emerged of him at a wreath-laying ceremony in Tunisia in 2014. He claimed he had been paying his respects to the victims of a 1985 Israeli airstrike, but admitted he had also been “present at”, though not “involved in”, a nearby ceremony in honour of four members of the Black September terrorist group behind the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, at which eleven Israelis were killed. The incident sparked a Twitter spat with Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, who said that Corbyn’s presence at the wreath-laying deserved “unequivocal condemnation”; Corbyn rejected the claims and responded: “What deserves unequivocal condemnation is the killing of over 160 Palestinian protesters in Gaza by Israeli forces since March”.

Later in August 2018, Corbyn was forced onto the defensive over a 2013 speech in which he declared that Zionists have “no sense of English irony”. He said he had used the term ‘Zionists’ in “the accurate political sense and not as a euphemism for Jewish people”, but the former Chief Rabbi Lord Sacks branded the comments “the most offensive statement made by a senior British politician” since Enoch Powell’s anti-immigrant Rivers of Blood speech in 1968.

In July 2018, Labour adopted a new code of conduct on antisemitism, but it fell short of the definition given by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The IHRA lists several examples of antisemitism, such as “claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavour”, that were omitted from Labour’s code. Critics of the IHRA claimed that its definition stifles legitimate criticism of Israel. However, Jewish leaders and some Labour MPs demanded that Labour accept the full definition. It did so in September, albeit with an accompanying statement that this would not “undermine freedom of expression on Israel or the rights of Palestinians”.

In February 2019 eight Labour MPs quit the party to form the Independent Group, which later became Change UK. Three Conservative politicians accompanied them. In her resignation speech, Luciana Berger said Labour had become “institutionally anti-Semitic”. Several of her fellow dissidents echoed this charge.

Their argument was given extra weight by an edition of the BBC’s Panorama programme that was broadcast in July. Labour’s National Constitutional Committee, which deals with disciplinary cases, is supposed to be independent. However, seven whistleblowers from inside the party told Panorama that members of Corbyn’s office had interfered in disciplinary cases relating to antisemitism.

Dan Hogan, a former investigator, claimed that on several occasions staff appointed by Jennie Formby “overruled us and downgraded what should’ve been a suspension to just an investigation or worse to just a reminder of conduct, effectively a slap on the wrist”. One of the specific allegations made against her was that she meddled in the case of Jackie Walker, who was suspended after claiming that Jews financed the slave trade. Corbyn was reportedly copied into the relevant emails. In response, Labour pointed out that Formby had been challenging a decision to delay the hearing.

Hogan and other whistleblowers levelled similar accusations against members of Corbyn’s team. One of these was Seumas Milne, the director of communications. He told party staff they were “muddling up political disputes with racism” and said Labour must “review where and how we’re drawing the line”. Sam Matthews, then the party’s head of disputes, characterised this as “the leader’s office requesting to be directly involved in the disciplinary process”. Labour said that Milne’s comments were taken out of context.

Another allegation was that staff at party headquarters were ordered to bring batches of antisemitism cases to Corbyn’s office for processing by his aides. Labour denied that this undermined the independence of the NCC.

Following the broadcast of the Panorama documentary, a party spokesman described the whistleblowers as “disaffected former officials” who have “worked to actively undermine [Corbyn’s leadership], and have both personal and political axes to grind.”

Either way, the revelations were just more material for the investigation launched by the Equalities and Human Rights Commission in May 2019 into whether Labour or members of Labour had committed illegal acts of discrimination or failed to respond effectively to such acts. Only the far-right British National Party had previously been placed under a similar investigation. For a party that prides itself on its anti-racism it was a dramatic fall from grace. As of July 2020, the report is yet to be published.

In October 2019, a year of parliamentary trench warfare over Brexit came to an end with the calling of another general election. The Conservatives, now led by Boris Johnson, ran on the slogan ‘Get Brexit Done’ and a promise of a bright post-Brexit future. Labour, torn between its mostly pro-Remain membership and its more pro-Leave voter base, doubled down on the left-wing message that had served it well two years earlier. Commentators wondered whether this might be a repeat of the 1983 election, when Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives trounced a Labour that was led by the left-wing Michael Foot and riven by internal divisions.

Comparisons with 1983 proved apt. Labour won 202 seats; the Conservatives won 365, giving them a majority of 80. Many Conservative gains came in northern England, in what was once Labour’s electoral heartland.

The day after the election, Corbyn announced that he would resign as Labour leader after a “period of reflection” for the party. Meanwhile, a successor had to be chosen. The field quickly narrowed to three: Lisa Nandy, the dark horse; Rebecca Long-Bailey, a key Corbyn ally; and Keir Starmer. Starmer, though viewed as a soft leftist, managed to appeal to the hard left by refusing to seriously criticise Corbyn during the campaign and by promising to keep the key elements of Labour’s 2019 manifesto. This combined with his perceived competence and electability won him 56.2% of the vote in April 2020.

In his victory speech he said, “Antisemitism has been a stain on our party… on behalf of the Labour Party, I am sorry. And I will tear this poison out by its roots”.

Within days of taking the helm Starmer held a video conference with representatives of four Jewish groups. He promised to set up an independent complaints system, to demand an immediate report on all outstanding cases, and to roll out antisemitism training for all Labour staff. The four Jewish groups later issued a joint statement, saying, “Starmer has already achieved in four days more than his predecessor in four years”.

Viewed in this light, the firing of Rebecca Long-Bailey looks like another step forward in the long battle against antisemitism. But politics does not go away. The move was praised by Jewish groups and many Labour MPs; Marie van der Zyl, the president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, said it showed Starmer was “backing his words with actions”, while the Labour MP Margaret Hodge said, “This is what rebuilding trust with the Jewish community looks like.” But many left-wingers reacted furiously. Some argued that Maxine Peake’s comment had not been antisemitic. Others condemned Long-Bailey’s firing on political grounds; Momentum, the Corbyn-backing movement, issued a statement saying that Starmer “says he wants party unity, then sacks the most prominent leftwinger on the frontbench”.

Another row erupted in July when Labour apologised for making “false and defamatory” comments about the whistleblowers who had spoken to Panorama. The party also agreed to pay damages. Opinion on the move was split along the usual lines. The Labour MP Ruth Smeeth described the whistleblowers as “inspirational”, but Corbyn said the settlement was “a political decision, not a legal one”, and “risks giving credibility to misleading and inaccurate allegations about action taken to tackle anti-Semitism”. It is noteworthy that Labour’s lawyers advised the party would win the case if it fought on.

No party is completely free of racism, but the controversies that have dogged Labour over the last four and a half years – allegations that the leadership failed to tackle antisemitism, that they actively interfered in antisemitism cases, that the leader himself was antisemitic – have tarnished the party’s reputation. They have also added another dimension to the struggle between a rejuvenated hard left, which came within touching distance of power, and the mainstream, which believes that only it has the wide appeal needed to win Labour its first general election since 2005. Repairing the damage in relations with the UK’s Jews will take time, but the party under Starmer is winning back their trust. Whether they can win back the trust of the electorate remains to be seen.

#antisemitism #labour #labourparty #uk #politics #ukpolitics #jeremycorbyn #news #breakingnews #politics #currentaffairs #politicians ##debate #controversy #hatespeech #socialmedia #rumours #election #debate #journalism #teenjournalism #reporter #reporting #corbyn #borisjohnson #tories #leftwing #conservative #rightwing

_edited.png)

Comments