Defying All Odds: Socialists Return to Power in Bolivia

- Raunaq Singh Bawa

- Oct 24, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 23, 2024

Less than a year after an alleged right-wing orchestrated coup d’état in the Latin American nation of Bolivia, the Socialists have returned to power in a landslide election, under the banner of MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo or Movement Towards Socialism)

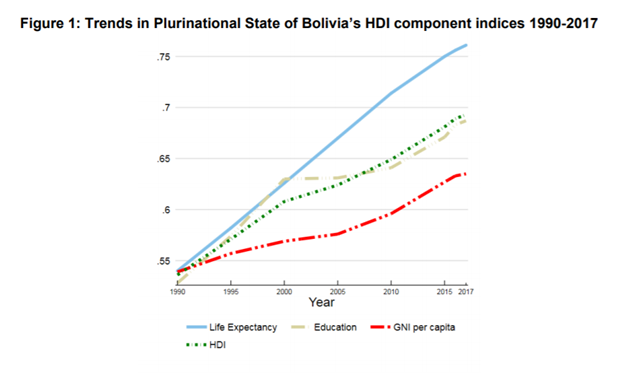

Veteran MAS leader Evo Morales led his small landlocked country as President for nearly fifteen years, from his first election in 2005 until his ouster amidst allegations of election fraud in late 2019. While still one of the poorest nations in Latin America, Bolivia has been steadily improving its HDI rankings from the 1990s onwards: a trend which remained consistent even with the introduction of Socialist ideology in 2005, contrary to popular perceptions of the ineffectual nature of socialism.

While being effective in improving standards of living and reducing substantially the bulk of the population living in extreme poverty, the regime was infamous for its attempts to cling on to power. While the 2005 Constitution of Bolivia, drafted under the Morales Presidency itself, allowed for only a single more consecutive re-election, every time an election came around the corner, this provision was extended.

Thus, it transpired that, through a series of elaborate legal and judicial acrobatics, Morales, who had come into power under a Constitution which prohibited consecutive re-election, ultimately retained power for 14 years in succession. In one instance, the Bolivian government and the Constitutional Court went so far as to declare that term limits are a human rights violation: a proposition that was refuted by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

However, despite these repeated and flagrant violations of constitutional law, Morales remained a highly popular leader, and elections were generally considered to be free and fair. Morales’ ‘peasant’ background and indigenous identity, coupled with his government’s ‘pragmatic socialism’, made him popular amongst the masses—something made evident by the electoral rewards bestowed upon MAS in the elections. For example, after the 2014 elections, Morales returned to power with 61% of the vote.

It was finally in 2019 that allegations of electoral fraud arose, expressed most vocally by the conservative-right in the country. The Organisation of American States (OAS), in its compiling of electoral data, claimed to have found certain discrepancies in voting patterns which were promptly attributed to electoral fraud, sparking massive outbursts by the political-right in the country.

Large-scale protests, coupled with the pressure exerted by the police forces and the army on the MAS Government, finally forced Morales to flee Bolivia, leading to a collapse of the MAS government and the installation of conservative Jeanine Anez as interim president.

However, the coup d’état itself came under fire, especially after use of disproportionate violence by the state against pro-MAS protesters, the majority of whom were indigenous citizens, in contrast to the mostly white constituents of the right-wing. Independent agencies like the Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic and the University Network for Human Rights conducted a study of the on-ground situation, where eye-witnesses complained of alleged “racist and anti-indigenous language” being used by government forces.

In the meanwhile, independent studies conducted by actors like the New York Times deduced that the OAS study of voting patterns was ridden with technical errors, resulting in misleading conclusions. Such conclusions reduced the legitimacy of claims that the 2019 elections were rigged.

Notable was the silence of the usually-verbose Trump administration, perhaps a consequence of Anez’s anti-Socialist policies, and actions such as the deportation of over 300 Cuban and Venezuelans from Bolivia. In fact, the only statements given by President Trump with regards to the 2019 crisis were those endorsing Anez, while comparing the erstwhile Morales administration to the “illegitimate” governments of Venezuela and Nicaragua.

It was finally after much disaffection that elections were conducted in October 2020, with a plethora of competing right-wing and centrist leaders. Representing the Conservatives was Fernando Camacho of the We Believe Party, while the MAS was represented by Luis Arce - a close associate of Evo Morales, and long-time finance minister in Morales’ administration.

While many observers expected Arce to have an edge—owing to his well-known competence as an economist, and the popular appeal of the Socialists—nobody could have predicted the nature of his win. The first round of elections was expected to result in a stalemate, leading to a second, which the right-wing hoped to win as a united front. However, dashing their hopes, MAS won an overwhelming victory, with 55% of the vote, securing an absolute majority in both Houses of Congress. It was clear to all that no second round of elections was needed to determine the winner.

The unprecedented nature of the Socialist win took all observers aback. However, greater challenges lie ahead for MAS.

As a consequence of political instability and economic mismanagement by the interim right-wing government, Bolivia has thus far shown a poor record in the face of the global COVID-19 pandemic, with the third-highest per capita death rate. Weathering this crisis will be the first rite of passage for the MAS as it returns to power with an overwhelming welcome from the people. Only time will tell whether Arce can bring his nation back on track, as the survival of Bolivian socialism hangs in the balance.

_edited.png)

Comments